Mar 2, 2022

The Early Years of Nursing in the Presidio

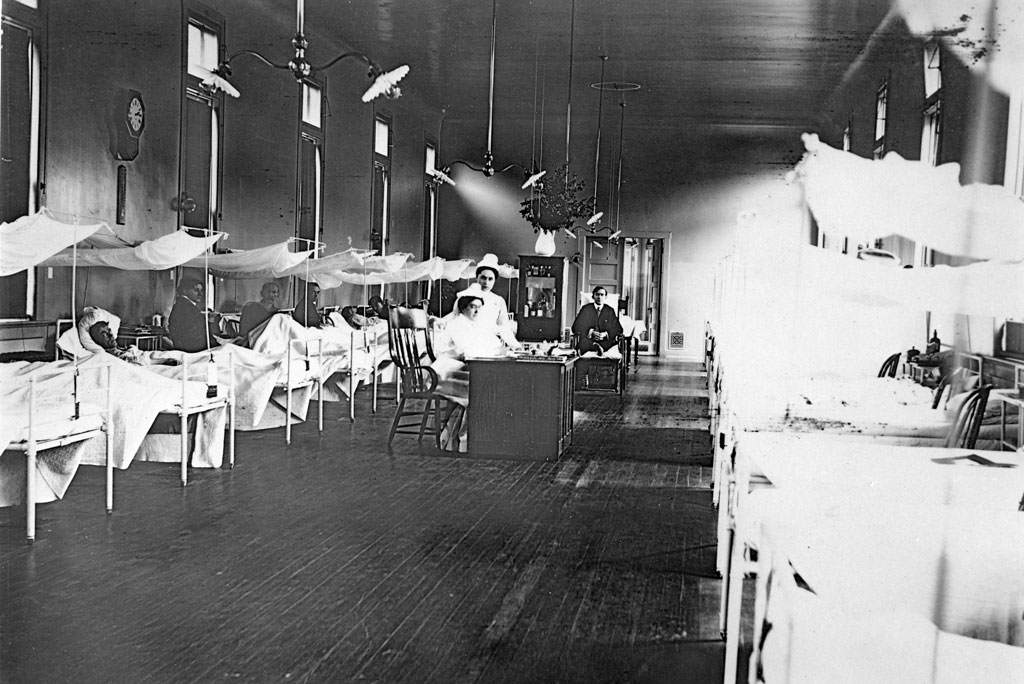

The Army Nurse Corps and Letterman General Hospital have their origins in the Spanish-American War.Both the U.S. Army Nurse Corps and Letterman General Hospital in the Presidio of San Francisco have their origins in the Spanish-American War. After the United States went to war with Spain over its treatment of Cuba in April 1898, the Army made hurried plans to expand its forces to 190,000 men – about seven times its peacetime size – to fight in the Spanish colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Pictured: Nurses, hospital corpsmen, and patients in a ward at Letterman General Hospital at Christmastime in 1901. Image courtesy of the GGNRA, Park Archives.

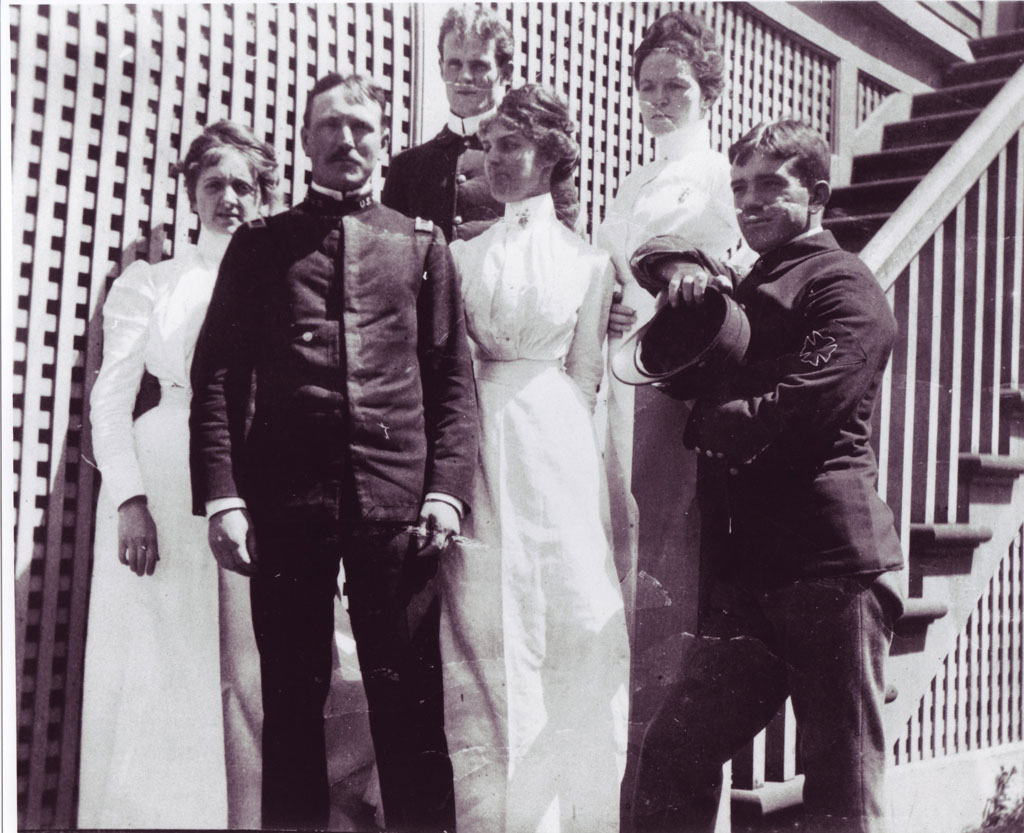

The Army Medical Department was unprepared to support such an increase in personnel, and Surgeon General George Sternberg quickly turned to hiring trained professional nurses on a contract basis, something the Army hadn’t done since the Civil War. By this time, raining for nurses had developed to the point where they were well prepared to support the complicated demands of modern medical care and treatment. Overall, 1,153 women served as contract nurses over the course of the war, and while not full members of the Army, they shared many of the same hardships and risks. Seeing that nursing saved lives, skeptical Army officers became supporters, and the Army has employed nurses ever since.

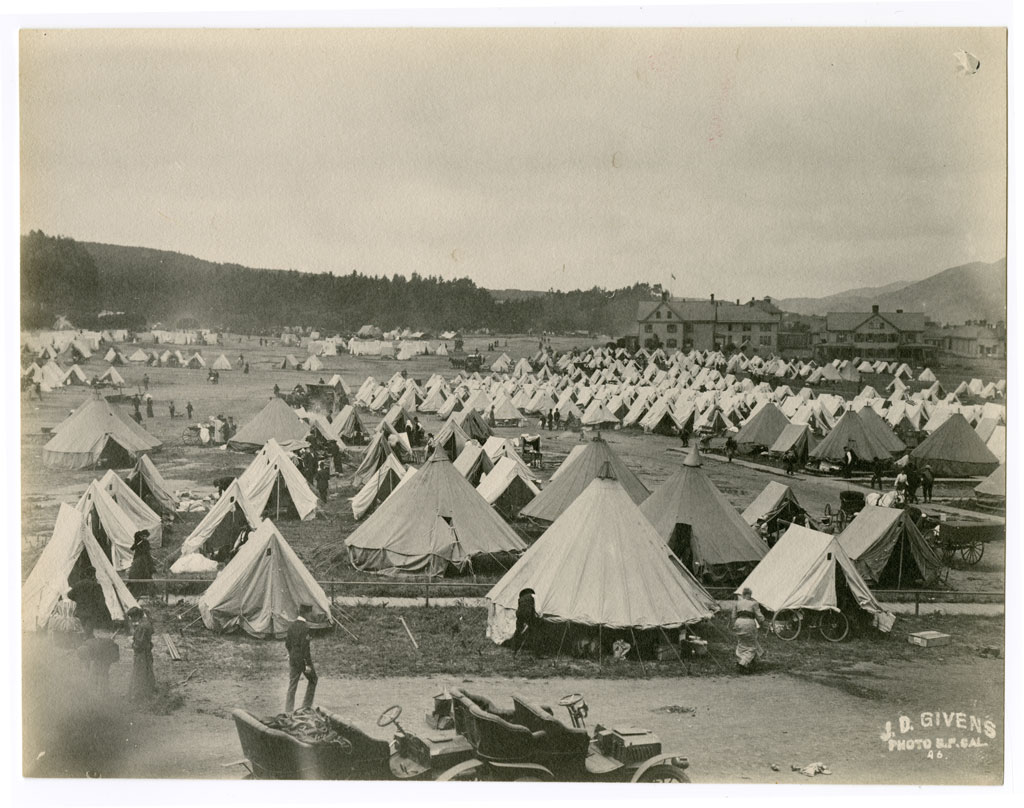

During the war, a few dozen of these contract nurses were stationed at the Presidio and other camps in the area to care for the roughly 22,000 troops that assembled for transport to the Philippines, which the U.S. later annexed after defeating Spain. Concerned that returning soldiers would need treatment for injuries, tropical diseases, and other illnesses, the Army on December 1, 1898 established a general hospital at the Presidio, which would later be named Letterman General Hospital in 1911.

Designed to accommodate 400 patients, when its new buildings were completed in July 1899, Letterman was soon overwhelmed after fighting broke out between the occupying U.S. forces and unanticipated Filipino resistance. For the next three years, Letterman admitted about 5,000 patients a year, only beginning to drop off as the major fighting ended in 1902.

Around the time of the completion of the hospital buildings, one nurse wrote in a letter:

Since I came here we have had no trouble of any kind. I found the nurses who were here, women who did their work well and were quiet and womanly in their behavior. The nurses who have been sent since have proven, with a few exceptions, all one could desire…Our work has been very heavy at times, and the patience and good work of the nurses under these emergencies is to be commended. We had thought that when we got settled in our new hospital everything would be fine; it is in many ways, and when the hospital is equipped (fully) it will be a very fine place. The subject of one mess has been a very trying one, but now it is arranged; we do not have any extra expense, and are living very well. (“United States Army Nurses,” The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 23, No. 2, September 1899, pgs. 140-141.)

The steady flow of patients made the Presidio’s Letterman General Hospital the busiest hospital in the Army. The thirty or so contract nurses on staff helped to maintain a valuable sense of order. In this period, the Army employed about 200 nurses at a time, and nearly everyone spent some time working at the hospital before shipping out to serve in the Philippines and again after returning.

Finally, after years of lobbying by Army medical officers and nursing leaders, and in recognition of the indispensability of nurses, Congress created the U.S. Army Nurse Corps as a component of the Medical Department on February 2, 1901. For the first time, women could serve in the Regular Army although it would take decades to give them the full equivalent ranks to men.

Letterman General Hospital was the first Army general hospital to employ the women of the Army Nurse Corps, and it remained the Army’s largest and most active hospital until World War I. During these first decades, most of the Nurse Corps trained or worked at the hospital at some point in their careers.

Some of the Nurse Corps’ nurses went on to occupy important positions, including the very first superintendent of the Corps, Dita H. Kinney, who had worked in the hospital’s operating room while a contract nurse.

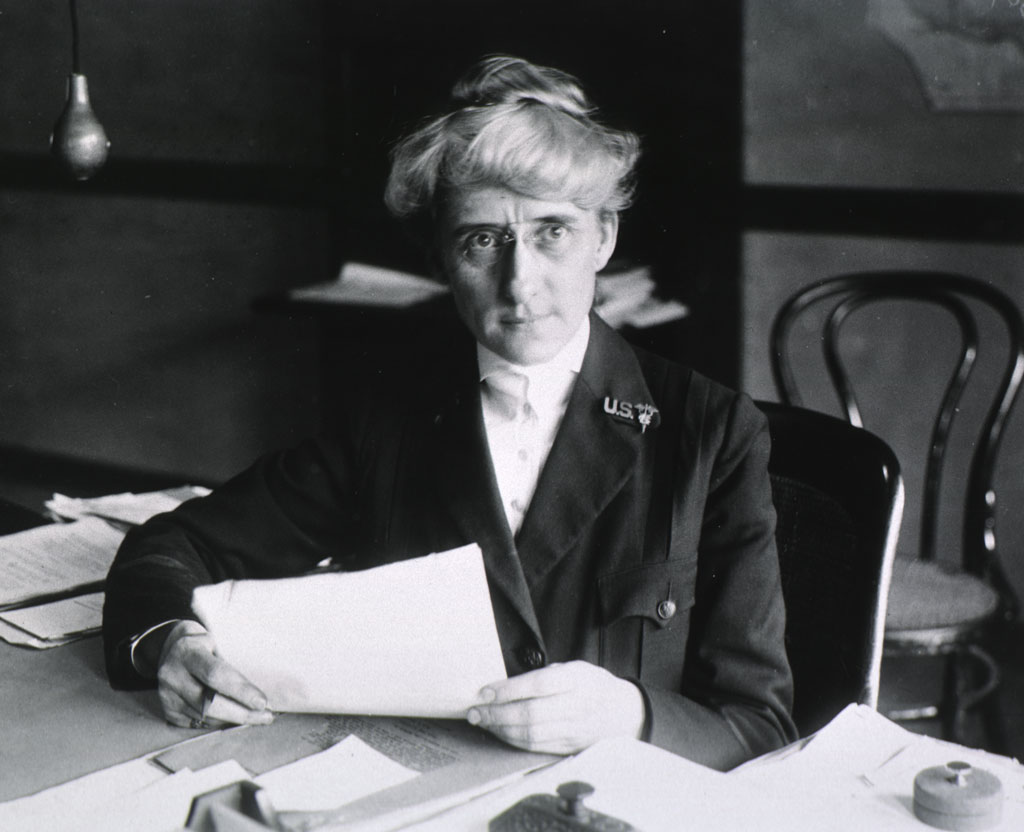

Another notable nurse was Dora E. Thompson, for whom Thompson Reach in the Presidio is named. Her first assignment when she joined the corps in 1902 was at Letterman, and three years later she became the hospital’s chief nurse.

Thompson led the nurses in the response to the earthquake and fire that hit San Francisco in 1906, the first time Army nurses operated in a civil relief mission. In addition to treating the injured, she helped to arrange accommodations for refugees and organized volunteer nurses. She later recalled: “Nothing was easy that day. In the midst of all the confusion, an ‘earthquake mother’ bore triplets – no less! (They all lived. They wouldn’t have dared not to.)” (Mary T. Sarnecky, A History of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, 58.)

In September 1914, the surgeon general, Brigadier General William C. Gorgas, selected Thompson to be the fourth superintendent of the Nurse Corps, in part because of a report on her work during the earthquake which emphasized “her executive ability, her high standards of conduct, impartial discipline, attention to duty, and persistent effort” (Mary T. Sarnecky, A History of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, 77). Three years later, after the United States entered World War I, she oversaw the expansion of the corps from under 400 nurses to 21,480 at its peak and supported their deployment overseas, work which earned her a distinguished service medal.

Superintendent Thompson later returned to Letterman as its chief nurse in 1922 and remained there until she retired in 1932.

Nurses at Letterman in the early years of the corps showed they were highly trained professionals, and that nursing was essential to maintaining an effective army – both in peacetime and wartime. They helped lay the groundwork for Army nursing for the rest of the century. In coming decades, Letterman nurses would continue to display this same resolve and professionalism as they faced the new challenges created by increasingly destructive instruments of war, and as they expanded their work to care for veterans and the families of servicemembers.