Jul 28, 2021

Buffalo Soldiers at the Presidio of San Francisco

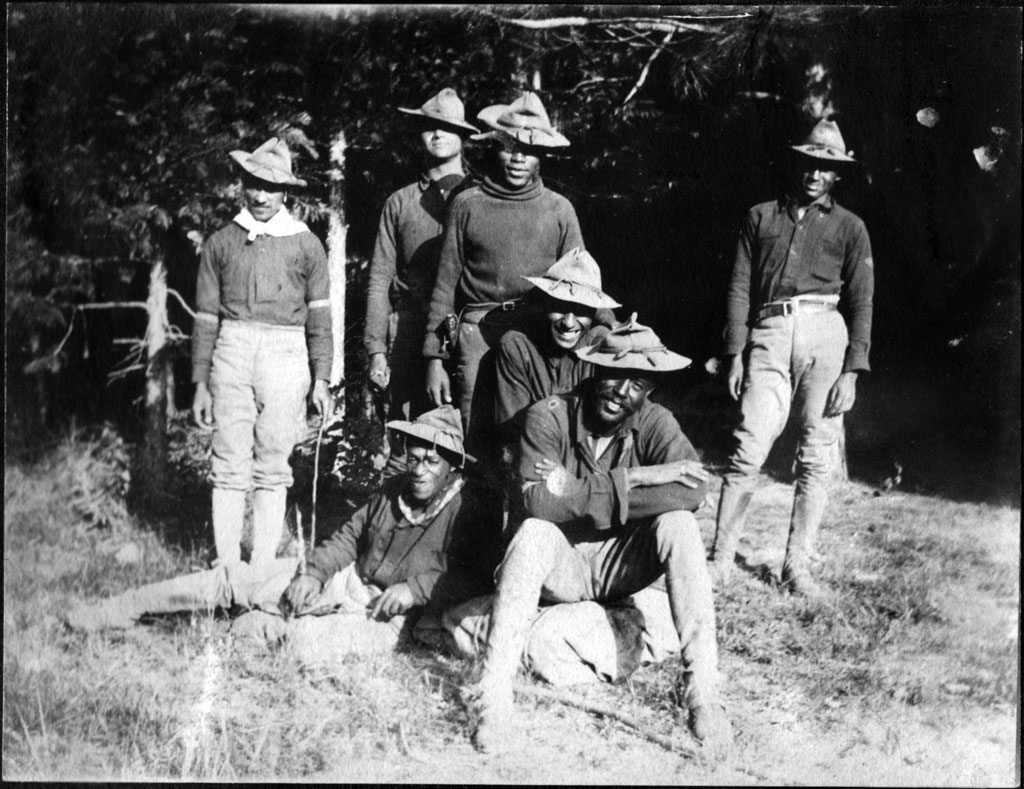

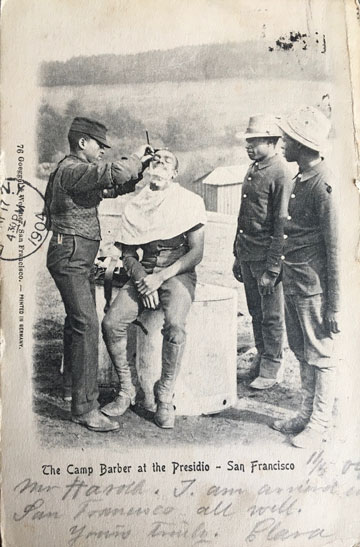

These African American regiments were among the first to protect national parks.Company H, 9th Cavalry in camp at the Presidio in 1900. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

On July 28, 1866, during the aftermath of the Civil War and in response to demands from settlers in the West for more troops, Congress passed an act to reorganize and enlarge the Regular Army. One component of this act revolutionized the Army by authorizing for the first time the creation of four black regiments of infantry and two of cavalry. Nearly 200,000 African Americans had fought for the Union in the Civil War, but never before had they been able to serve in the permanent U.S. Army. Together with the opening of West Point to black cadets, this moment in history served as a significant victory for the African American community.

In 1869, congressional reductions in the size of the Army led the War Department to consolidate the four infantry regiments into the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments. In the 1870s the black men of these units together with the soldiers in the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry Regiments came to be known as “Buffalo Soldiers.” They made up ten percent of the Army from 1869 to 1898 and were commanded almost entirely by white officers.

These soldiers spent most of their time serving at small, isolated posts in the west, performing the same duties as other units – such as maintaining order, making sure Indians stayed on reservations except when they were allowed to hunt, keeping white intruders out of reservations, escorting rail construction crews, and building roads and telegraph lines.

The Army didn’t station any of these units at the Presidio of San Francisco until 1899. This was in part because the Presidio was primarily a post for artillery units, but it was also because of the Army’s reluctance to place black soldiers in major cities where whites could cause friction. What ultimately brought these soldiers to the Presidio was the Philippine War, which was a result of the US annexation of the Philippines at the end of the Spanish-American War.

In April 1898, the US declared war on Spain with the stated purpose that they were liberating Cuba from Spanish control. The Army sent a military expedition to occupy Manila in the Philippines, which was then part of the Spanish Empire. At the end of the war, Spain ceded control of the Philippine islands to the US, giving the United States its first major overseas territory. However, a widespread insurgency of Filipinos refused to accept American rule, and fighting with the Army broke out around Manila on February 4, 1899. The US soon rushed available Regular Army units to the Philippines, including the Buffalo Solider infantry units.

The 24th Infantry Regiment – 1899

The first black Regular Army units to come to the Presidio arrived on April 7, 1899. The Headquarters, Noncommissioned Officer Staff, and Band of the 24th Infantry Regiment traveled by train with Companies H and L from Fort Douglas, Utah, while Companies E and I came from Fort D.A. Russell, Wyoming.

They arrived in Oakland and – except for Company H – boarded the Army steamer Irvin McDowell to cross the San Francisco Bay to the Presidio wharf and march into camp. Company H went to the Army post at Alcatraz Island. They were welcomed by the local African American community with banquets and picnics, and for the next few weeks, the regimental band played at concerts and events around the Presidio and the City for both black and white audiences.

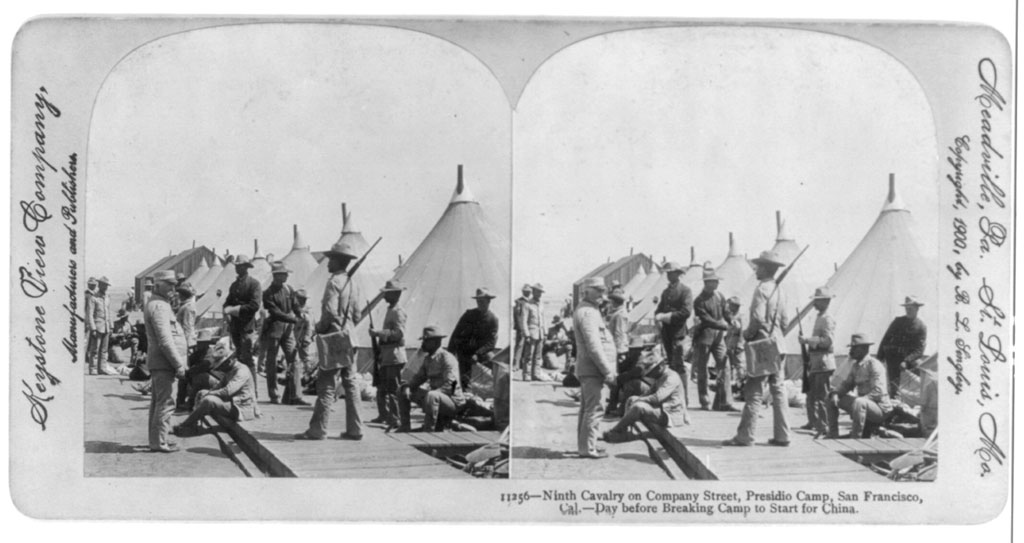

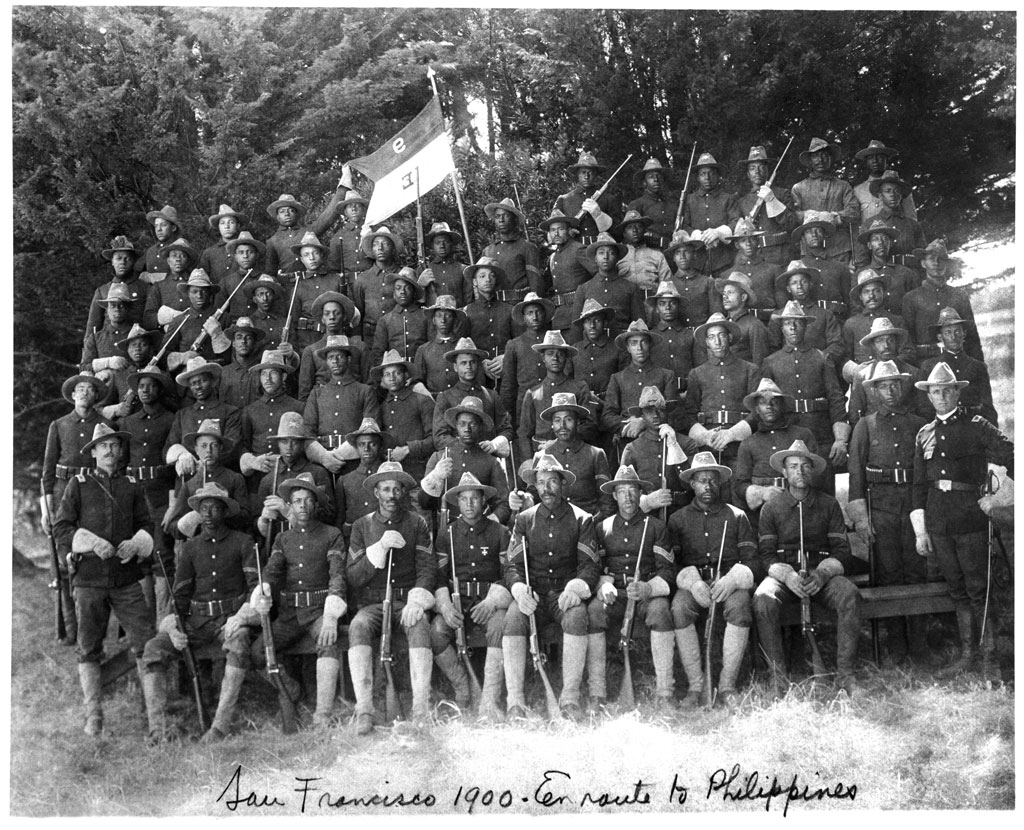

Over the next four months, four more companies of the 24th and eight companies of the 25th Infantry Regiment spent some time in camp at the Presidio before making the 6,600-mile trip across the Pacific Ocean to the Philippines, the last departing July 13, 1899. Troops of the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments passed through in 1900 and 1901 as the Army’s counterinsurgency operations continued. The Army allowed the wives and children of some of these enlisted men to remain in the Tennessee Hollow Watershed area of the Presidio while the units were abroad, as indicated in the 1900 census records.

While many African American leaders were critical of the war and US imperialism, the Buffalo Soldiers largely remained dedicated to their promised service, even while being openly critical in letters home of the racism they witnessed from white soldiers. Desertion from these units remained low. We also know from their letters and other accounts that many felt a sympathy for the Filipinos and the racism they endured. They typically had better relationships with the Filipinos, which helped to bring an end to the insurgency.

The insurgency collapsed in 1902, and governance of the Philippines passed from the Army to American civil control. The Army maintained about 12,000 men in the Philippines for the next few decades, and elements of all of the Buffalo Soldier units did several tours there between 1899 and 1915, usually passing through the Presidio on the way to or from the islands. Several accounts mention how they stayed in the Model Camp, located near the Lombard Gate, roughly where the Letterman Digital Arts Center is today.

The Army in the National Parks

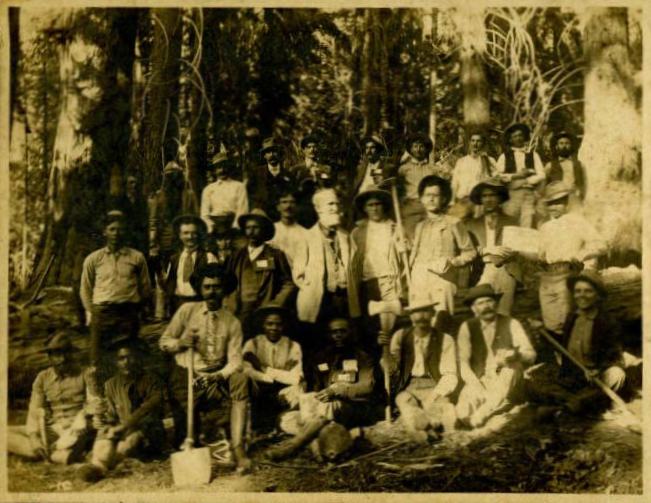

In 1899, transport to the Philippines for the 24th Infantry was delayed after they arrived at the Presidio. While they waited, the Army sent a detachment of thirty men from Companies E and I to Sequoia and General Grant National Parks in California on May 2, and a detachment of Company H from Alcatraz to Yosemite National Park.

Since the National Park Service wasn’t created yet, the Army had been responsible for guarding and stewarding these national parks with cavalry patrols sent every summer since 1891 from the Presidio. This was the first time that black soldiers performed the duty. No official report survives, but they probably performed the usual duties of protecting the parks from poachers, shepherds, and other trespassers. They were only able to stay a few weeks there and returned to San Francisco to ship out with their regiments in June.

The Ninth Cavalry – October 1902 to October 1904

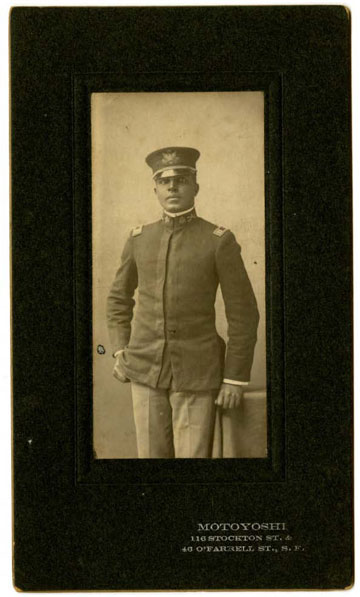

While most of these units only spent a brief time at the Presidio, when the Third Squadron of the Ninth Cavalry – Companies I, L, K, and M – returned from the Philippines on October 13, 1902, it remained in garrison for the next two years. Troop I was commanded by Captain Charles Young, the highest-ranking African American officer in the Regular Army at the time.

Young was the third black man to graduate from West Point in 1889. He took command of Troop I in April 1901 while it was in the Philippines. Young was well known and well regarded in the African American community for his work as a professor of military science at Wilberforce University, for his service in the Regular Army, and as a major of the Ohio National Guard during the Spanish-American War.

As a leader in the community, Young encouraged young black men to maintain their determination and strength of character in the face of the daily racism they encountered. He was a close friend of historian and educator W.E.B. Du Bois and while at the Presidio he was visited by prominent black leaders, including Booker T. Washington and T. Thomas Fortune. Also, during his time at the Presidio, he met Ada Mills of Oakland, and they were married in a quiet ceremony on February 18, 1904, which was attended by a few of his soldiers.

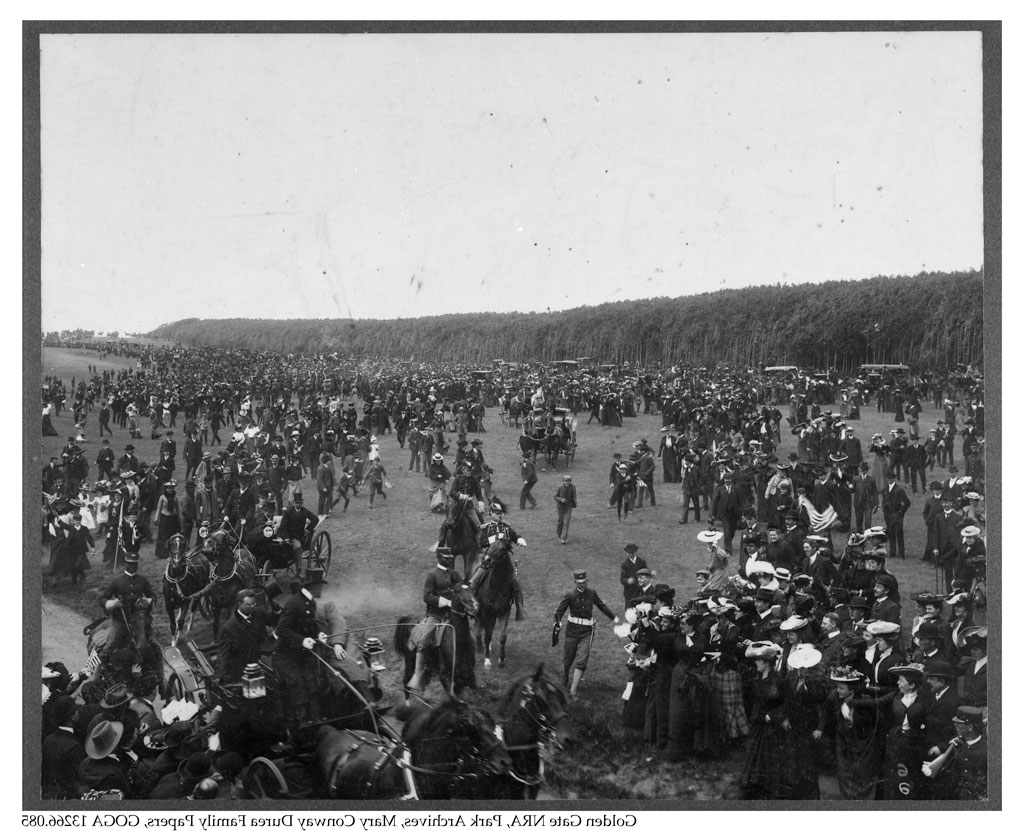

Besides the usual garrison duty, Troops I and M served as the honor guard for President Theodore Roosevelt during his visit to San Francisco on May 12 and 13, 1903. Shortly afterwards, a detachment of these troops led by Captain Young traveled to Sequoia and General Grant National Parks for their turn as park rangers and Young became the first black national park superintendent.

Preventing trespassers at these parks was less of a problem than it had been in previous years. Instead, the soldiers’ work focused on accommodating the growing number of tourists. Under Young’s supervision, his soldiers and civilian contractors completed the wagon road to the Giant Forest – the most famous grove of Giant Sequoias in the park – and another two miles to Moro Rock. Meanwhile, enlisted men repaired about eighteen miles of trails and began work on two new trails between Lone Pine and Mountain Whitney. Young’s final report reveals the mind of a thoughtful conservationist who was ahead of his time.

The 24th Infantry and the Panama Pacific International Exposition, 1915

On September 12, 1915, Company L of the 24th Infantry arrived at the Presidio from the Philippines, followed by most of the rest of the regiment on October 12. They took up residence in the Montgomery Street Barracks, planning to stay several months. As the San Francisco Chronicle wrote: “The command has been sufficiently long in the Philippines to entitle it to a desirable post for a time instead of sending it down for border patrol duty shortly after it lands. It is a splendid regiment and Army men believe that San Francisco will find it just as desirable a command, from the standpoint of orderly conduct, as any regiment in the service.”

At the time, San Francisco was hosting the Panama Pacific International Exposition, a world’s fair celebrating San Francisco’s recovery from the 1906 earthquake and fire, as well as the recent completion of the Panama Canal. About half of the fair was located on Presidio grounds – occupying what today we call Crissy Field – and some neighboring areas.

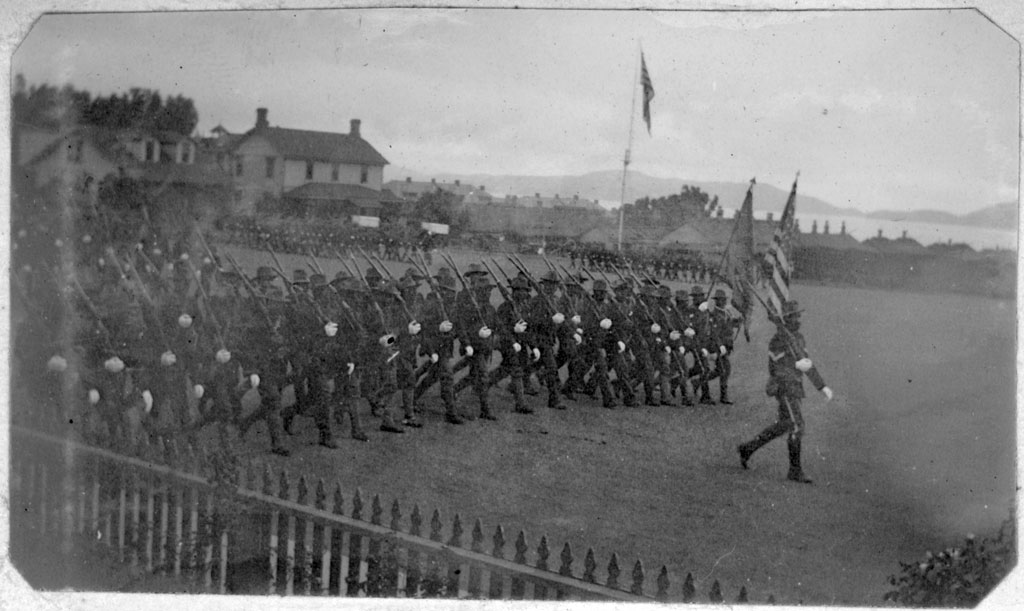

Between its arrival and the end of the fair in December, the 24th Infantry represented the Army to the thousands of visitors who came every day. The men performed guard duty, demonstrated drills, and its band performed regularly. It also participated in many official events, including San Francisco Day on November 2, escorting the Liberty Bell from the Tower of Jewels to the Southern Pacific rail yards, Army Day on November 29, and the closing ceremonies of the fair in December.

The Buffalo Soldiers left the Presidio for Wyoming in February, and a few months after that, found themselves again in service in another country when they went to Mexico as part of the Punitive Expedition.

The San Francisco National Cemetery

A lasting memorial to the service of the black regulars is the San Francisco National Cemetery in the Presidio. The National Park Service and the Presidio Trust have identified 460 Buffalo Soldiers buried there. Many served in the Spanish-American and Philippine Wars.

Among them is Medal of Honor recipient Private William H. Thompkins of the 10th Cavalry. During the Spanish-American War, Thompkins and three other black soldiers voluntarily rowed a boat ashore under heavy fire to rescue trapped and wounded US and Cuban soldiers at Tayabacoa, Cuba, without taking any losses.

Visitors can honor the memory of Buffalo Soldiers by visiting their gravesites at the San Francisco National Cemetery. Learn more about Buffalo Soldiers in the Presidio through this brief video featuring retired Ranger Rik Penn, or through an exhibit at Fort Point.